May 2, 2022

Vagabond’s Note: This is the first in a series of four installments chronicling the interactions between the American Military and the Lenape or Delaware Native American people during the time of the American Revolution.

Even though the Squaw Campaign took place in Pennsylvania, it involved men from this area and the impact of it affected the history of Ohio as well as Virginia and Pennsylvania. The other three events in this series all took place in Ohio.

At the end of each story, I will provide a set of GPS coordinates which you can use to visit the locations of the events discussed in the story. Instead of “Geocaching” we will play “Geo-History.” If you are unable to visit those sites in person, you may also copy the coordinates and paste them into the search box in Google Earth to see those places.

In the summer of 1776, General George Washington put out a call for volunteers from Pennsylvania and Virginia to build his army. During July, August and September, just over 400 men answered that call and reported to Kittanning, PA where they became the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Army. On February 12, 1777, another group of men reported to Fort Pitt where they became the 13th Virginia Regiment.

Both of these units included men from Western Pennsylvania and West Augusta, VA (which is now part of northeastern West Virginia and Southwestern Pennsylvania). Captains Sam Brady and Van Swearingen, from Westmoreland County, PA, served in the Eighth Pennsylvania and Benjamin Biggs from Ohio County, VA, served in the Thirteenth Virginia. Both of these regiments saw battle while serving in the Continental Army and both spent the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge.

Photo by Vagabond Historian

While the men from western Pennsylvania and Virginia were away from home serving in Washington’s army, some of the Native Americans who supported the British waged terrorist warfare on the unprotected families of those volunteers. As word of the brutal raiding parties reached Washington’s army back east, the men began deserting to go home and protect their families. The Valley Forge records include a number of trials for those desertions.

In addition to the raiding parties, some members of the Native American army joined forces with the British who were headquartered at Fort Detroit. On September 1, 1777, the Native Americans and British jointly attacked Fort Henry at Zanesburg (Wheeling) – threatening the entire western portion of the newly formed United States.

In response, Washington sent an experienced army officer named General Edward Hand to Fort Pitt to assume command and organize the Western Department of the Continental Army. General Hand took command of Fort Pitt on June 1, 1777 relieving Captain John Neville (who had taken over during the summer of 1775 after John Connolly was forced to leave Pittsburgh). When Hand arrived, he found himself in command of an undisciplined collection of militia companies from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania and Ohio County, Virginia. To make matters worse, the Virginia and Pennsylvania militia units disliked working with each other because of the disagreement over which colony owned the district of West Augusta where Fort Pitt was located. In December, 1777, Hand wrote a letter to Washington describing the unorganized and undisciplined nature of the militia units.

Around the second week of June, 1777, Hand received the first of two letters from Reverend David Zeisberger, at Shoenbrunn on the Tuscarawas River in the Ohio country, informing him that Native Americans and British were assembling an army to destroy Fort Henry and the surrounding town of Zanesburg (Wheeling). In response, Hand sent five Virginia militia companies to reinforce the fort and sent orders to Colonel Andrew Swearingen at Holliday’s Fort instructing him to provide supplies to Fort Henry. Holliday’s Fort was located at the site of present-day Weirton, WV. Wyandot Chief Pomocan (AKA Half King) led the attack which took place on September 1, 1777. Although Pomocan was an excellent combat general, the inhabitants of Zanesburg were prepared for the attack and were able to defend the fort.

Photo by Vagabond Historian

Not long after the attack on Fort Henry, Zeisberger notified Hand that the British were planning to build a fort and munitions depot near the mouth of the Cuyahoga River on Lake Erie to provide weapons and supplies for Native Americans who were assisting the British. According to the information, the British planned to ship munitions and supplies to the new depot by boat from Fort Detroit.

In response, Hand put together an army of around five hundred Westmoreland County, PA and Ohio County, VA militiamen to travel to the mouth of the Cuyahoga River and destroy the munitions depot before it could be put into service. Col. Providence Mounts, Col. William Crawford, Major Brenton, William Brady, and Lieutenant Simon Girty all joined the expedition.

Around the middle of February, 1778, the army headed north along the Ohio River with plans to follow the trails north along the Ohio, Beaver and Mahoning Rivers then northwest to the mouth of the Cuyahoga. When the expedition set out, the frozen ground was covered by several inches of snow, but the weather warmed and it began to rain. The rain and melting snow sent the streams over their banks and turned the countryside into a muddy mess. Streams that normally were ankle-deep became swollen rivers that the men were forced to swim across or detour around. One man drowned attempting to cross a swollen stream.

About 15-20 miles south of the confluence of the Mahoning and Shenango Rivers at the headwaters of the Beaver River (where Newcastle, Pennsylvania is located today), the men began to see large numbers of tracks left by the Native Americans. Hand sent scouts ahead to reconnoiter. When the scouts returned, they reported that they had discovered a Native American village at the forks of the river. The scouts reported that 50-60 Native American warriors were at the town.

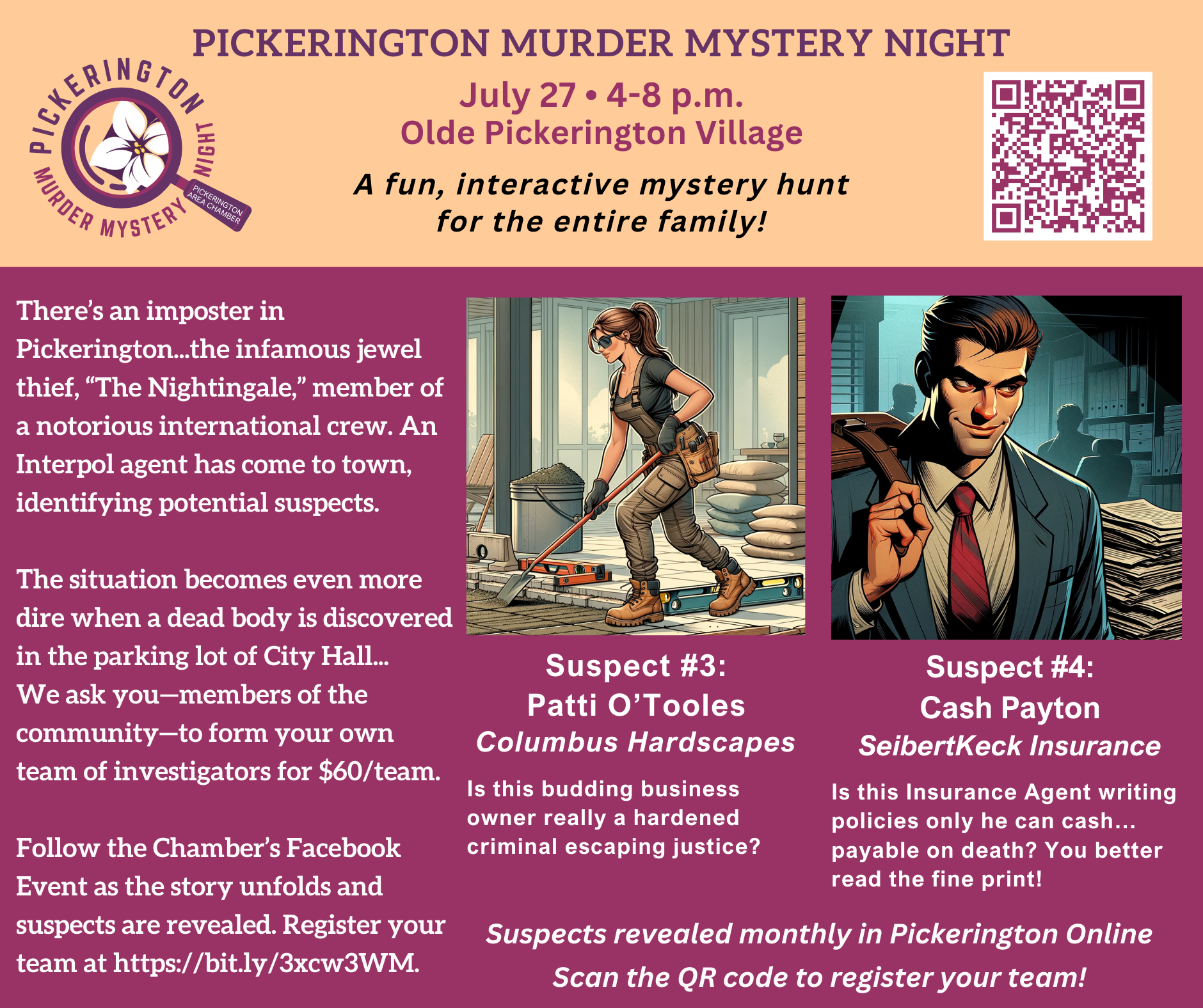

The village was a small Munsee town. The Munsees were part of the Lenape or Delaware Nation. Three clans made up the Lenape Nation: The Turtle Clan, the Turkey Clan and the Wolf Clan. Munsee was another name for the Wolf Clan. Most of the Lenape people were peaceful and remained neutral during the war with the exception of a few members of the Wolf Clan who had joined the Wyandots to support the British.

The Munsees living in the town had maintained neutrality as the war broke out between the colonies and the English, but that didn’t matter to the undisciplined militiamen. They surrounded the town and attacked. However, most of the men from the town were away hunting, so the only occupants of the town were old women and a few children. One of the old women there was Delaware Chief Pipe’s mother. She was shot several times then John Hamilton killed her with a tomahawk blow to the back of the head after which someone scalped her.

Chief Pipe’s brother along with his wife and children were also in the town. The wife and children managed to escape into the countryside through a gap in the militia encirclement left by Col. Mounts’ unit. Pipe’s brother stayed to defend his mother. Pipe’s brother got off one shot which wounded Captain Scott in the arm before he was shot several times. Then, Reasin Virgin killed him with a tomahawk blow to the head. (Some accounts state that some of Pipe’s brother’s children were also killed, but the eyewitness accounts that I read did not say anything about that.) The entire attack on the village was over in a matter of minutes. The only survivor was one old woman who had a finger shot off. The militiamen asked her where the men from the village had gone and she told them that almost everyone was on a hunting expedition with the exception of a few who had gone to a salt lick about ten miles upstream.

Simon Girty and Major Brenton missed the attack on the Munsee town. When the army broke camp that morning, Brenton discovered that his horse had gotten loose during the night and was nowhere to be found. As the army moved on, Girty volunteered to stay behind with Brenton to look for the missing horse. After several hours of searching, they found the horse and headed north to rejoin the army. By the time they reached the forks of the river, the attack on the village was over.

Photo By Vagabond Historian

Girty volunteered to lead a detachment of militia upstream to the salt lick to search for more villagers. When they arrived, they found four old women collecting salt and a young boy with a small caliber rifle who appeared to be hunting birds. Several of the men fired at the boy and then got into an argument about who should get credit for the kill. Since Girty was in charge, he declared that Zachary Connell should receive credit for the kill giving him the honor of collecting the boy’s scalp. In the meantime, some of the other militiamen opened fire on the old women killing all four of them. (One eyewitness account said that one of the women was taken prisoner and the rest were killed. Others say that all four were killed.) After collecting the old women’s scalps, the party rejoined the rest of the army.

Because the countryside was such a muddy mess, General Hand decided that reaching the mouth of the Cuyahoga was not possible, so the army headed back to Fort Pitt. By the time the men arrived at Fort Pitt, they were already being hailed as heroes for killing the unarmed women and the young boy. People were calling the excursion “The Squaw Campaign”. It is still known by that name today. In his report, Hand described his casualties as “one man drowned and one man wounded in the arm.” The general was appalled by the savage behavior of the poorly disciplined militiamen.

In May, 1778, General Hand sent a letter to George Washington and a letter to the Continental Congress asking to be relieved of the command at Fort Pitt and reassigned to the regular army back east. In response to Hand’s letter and to strengthen the Western Department, Washington sent the eighth Pennsylvania and the thirteenth Virginia regiments to Fort Pitt in the spring of 1778. Washington also sent a letter to General Hand assuring him that his request for transfer back east would be met as soon as a suitable replacement could be found. In his letter, Washington also told Hand that he had looked in on Mrs. Hand (who had been ill) and found her to be well. In August, 1778, General Lathan McIntosh replaced General Hand at Fort Pitt as commander of the Western Department.

The Squaw Campaign represented a dark day in our early American history and it impacted events later in the war. In spite of the murder of their brothers at the forks of the Beaver River, the Delaware chiefs sought to make peace with the Americans and to remain neutral. They signed the Treaty of Fort Pitt later that same year which the Americans would break only a couple of years later with the massacre at Coshocton.

The next installment on this series will describe the Treaty of Fort Pitt and the McIntosh Expedition of 1778-1779 including the building of Fort McIntosh at the junction of the Ohio and Beaver Rivers, the building of Fort Laurens on the Tuscarawas River (at a site just south of the modern-day town of Bolivar, Ohio), and the Siege of Fort Laurens during the winter of 1779.

Geo-History

Listed below are the GPS Coordinates for some of the locations mentioned in this story. You can copy the GPS coordinates below and paste them into Google Earth to see where those sites are located, but it is more fun to visit those places in person.

- Kittanning, PA where the Eighth PA was mustered into the Continental Army in September 1776

GPS Coordinates: 40° 48.513′ N, 79° 30.948′ W (Located alongside Rt 422 in Kittanning)

This is also the site of the Lenape Indian town by the same name which was destroyed by Colonel Armstrong after the Indians killed his brother at Fort Granville in 1756 - Site of Fort Pitt where 13th VA was mustered into the Continental Army

GPS Coordinates: 40° 26.468′ N, 80° 0.597′ W

This site is located at the Point in Pittsburgh, PA - The site where the where the Squaw Campaign massacre took place in 1778

GPS Coordinates: N 40° 59.634′, W 80° 21.341′ (On Atlantic Avenue in Oakland, PA) - Location of Fort Henry in Zanesburg (In Wheeling, WV today) Historical Marker

GPS Coordinates: 40° 4.145′ N, 80° 43.462′ W - Site of the Schoenbrunn Village Historical Marker

GPS Coordinates: N 40° 28′ 01.98″, W 81° 24′ 48.05″

This marker is located at the entrance to the Schoenbrunn Village Historic site. If you plan to visit the site in person, you will want to do so in the summer because the historic site is not open during the winter months.

If you are unable to visit the locations in person, simply copy the coordinates and paste them into the search box on Google Earth. Then use the street view to try to find the historical marker shown earlier in this story. Have fun!

Thanks for taking time to read my story. Please contribute your comments! – VH

Please also check out previous installments of this series:

– Geohistory: Flint Ridge

– Geohistory: USS Shenandoah

– Geohistory: Sears Mail Order Houses

– Geohistory: 135th Ohio Infantry at Andersonville Prison